Mo'Ne on the mound?

In a new RSA blog, Ben Dillot writes

As part of our new project with the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, we’ve been looking at the data on earnings, wealth and debt. And while some of the findings are unsurprising, there are a few curveballs in there too.

Let's step up to the plate and see what they're like. The first is ….

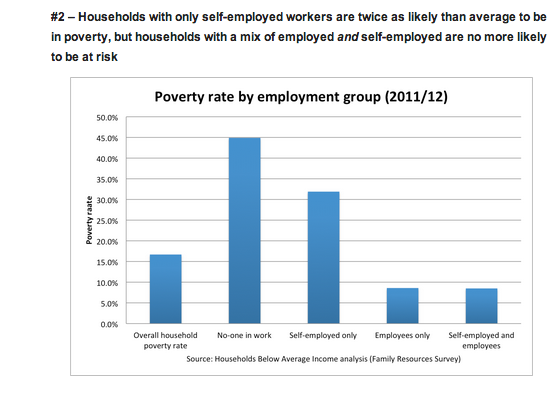

Not too difficult to read. If it is actually the security of a pay packet (copyright @CCHQPress) that is the best guard against poverty, nothing too puzzling about the fact that households with a mix of employed and self-employed are at about the same low risk of poverty as those with employees alone. It’s like measuring the risk of being hurt by a volley of arrows depending on whether you have a sword (self-employed) or a shield (employee). Clearly those with swords only are at a high risk of being hurt – they might be able to fend off one or two arrows but some of those arrows will hit home. Those with empty hands (out of work) are fairly helpless. Those who have a shield to shelter behind have a much lower risk of harm, but giving a sword to those who already have a shield won’t add much extra to their defences.

Next up is ...

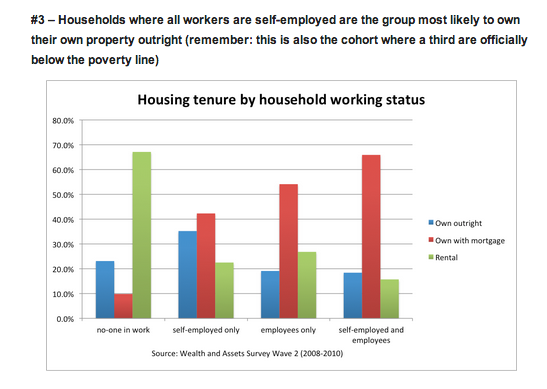

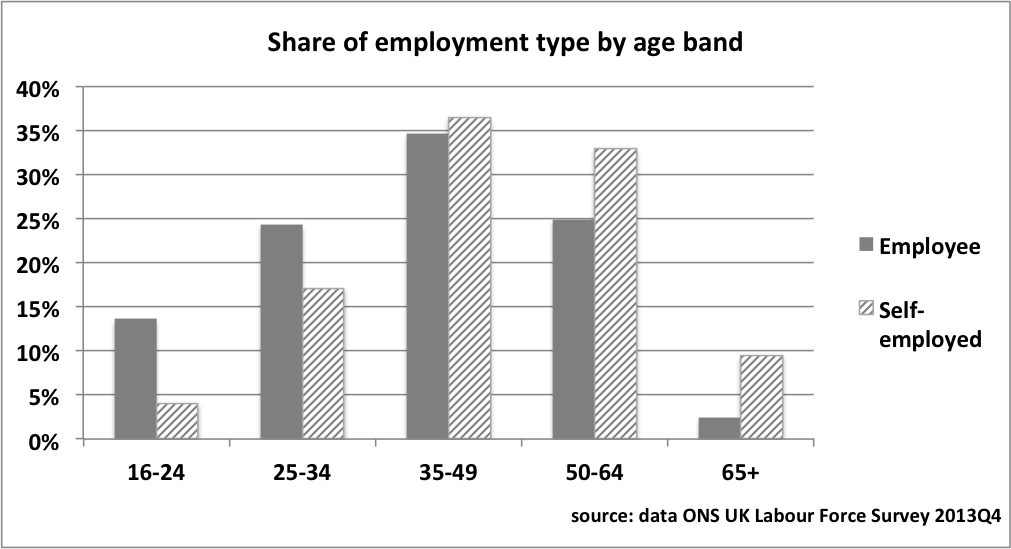

Why might the self-employed be more likely to own their homes outright despite a third being below the poverty line? A clue to possible reasons for this is given by looking at the group with the next highest levels of outright home ownership – households with no one in work. Most of these home owners will be people who paid off their mortgages during a life of work. It seems very likely that one reason for higher outright home ownership among the self-employed is that older people form a much higher proportion of the self-employed than of employees. Not far off half of self-employed people are 50 or over, by which age mortgages will have started to have been paid off, compared with just over a quarter of employees.

Here's the third pitch ...

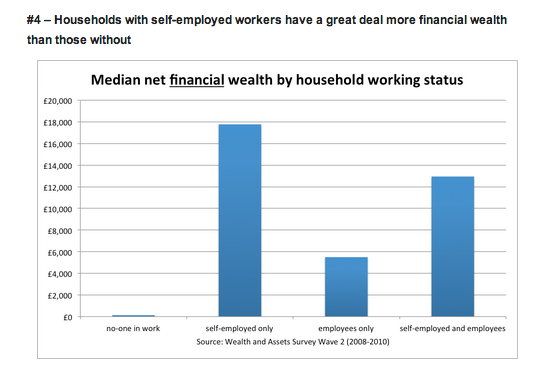

The point about home-ownership applies equally to the finding that median net financial wealth is greatest for people in self-employment, because they include significant numbers who have accumulated wealth over a lifetime. However, it's also the case that whatever form the wealth takes it is associated with employment status now.

The fact that people who are presently self-employed have a lot of wealth doesn’t necessarily mean that their wealth derived from self-employment or that the self-employed are more likely to save or invest. For many of them, their property and financial assets will have been acquired during employment as an employee. This won’t just be older people who have moved to self-employment as an alternative to retirement, but will also include 40-something employees who are financially secure enough to afford to strike out on their own. On their first day of self-employment they might own their property outright and have a fair-sized financial cushion of savings and investments, but none of their wealth will have derived from self-employment. Ben does allude to this at the very end of his post saying

‘does the nature of self-employed work encourage and enable people to save and stow away cash, or are the already wealthy simply more willing and able to work for themselves (and to survive on low incomes)?’

But this contains a bit of a false distinction and so isn’t really the right question. There is a strand of self-employment typified by career self-employment – some high-earning like barristers and similarly some lower-earning like minicab drivers. There is another strand that typically does not span a working life. Some of this is ‘opportunity’ typified by people with experience who decide to go it alone or start something up, but again this has a high-earning component of entrepreneurs and consultants and a lower-earning component of freelance journalists and home-hairdressers. Some will be already wealthy, but many will not be, and there won’t necessarily be any relationship between their previous and future incomes – some will earn more from self-employment and some less.

And finally there is ‘necessity’ self-employment resulting from loss of employee jobs, barriers to becoming an employee, welfare changes and all sorts of other reasons. They certainly won’t be wealthy enough to survive on low incomes nor will self-employment enable them to save and stow away cash.

All of this can be obscured by averages that treat the self-employed as a homogenous whole. As I’m sure that Ben knows this, his description of the points he illustrates as ‘curveballs’ might well be a tease. But just in case ….

Some other puzzlers ...

Resolution Foundation

The newly self-employed are likely to be suffer from some vulnerability and insecurity. But they don't appear to be much different in any key characteristic from the existing self-employed. Link to their report is here

Morgan Stanley

There are five key drivers of increases in UK self-employment. Overall these suggest the growth derives from weakness in the economy and is a sign of slack. Their report should download here.

Steven Toft (@FlipChartRick)

Increased self-employment doesn't appear to be necessarily a good thing, looked at internationally and macro-economically here

Benedict Dellot from the RSA

Growing self-employment results from opportunity not necessity, and suggestions to the contrary are myths to be busted here

Adam Lent from the RSA

High self-employment rates aren't a sign of economic weakness, but stirring entrepreneurial spirit here

TUC

The growth of self-employment is part of a trend towards casualised work, likely to hold back wages, and prevent people from having the kind of secure employment they need to pay their bills, save money and plan for the future here

Jonathan Portes

Writing in Financial World, Jonathan puzzles over the lack of productivity rebound from recession, and wonders whether ground has been lost permanently here.